Co-published with Acadiensis blog.

James Barry (1822-1906) was a Six Mile Brook, Pictou County miller, printer, fiddler, iconoclast, and curmudgeon. Born, like so many Pictou County folk, into the Presbyterian church, over his life he became intensely critical of Christian theology. His route is visible in outline, but the details are less clear; his diary, detailed in so many ways, offers no “Eureka” moment. But there are clues. Most of those clues, I argue, stem from his immersion in text – that is, that he saw text as defining the world, and thus critical engagement was necessary to properly understanding it. Very early in life, Barry distanced himself from both free church and Church of Scotland Presbyterianisms. By the time he was in his 30s, he was describing himself as a Morisonian, a small sect of Scottish Presbyterians defined mostly by their rejection of any form of church government. In the 1840s, 50s, and 60s, his Morisonian thinking was certainly more radically individualistic and textually-focused than that of his Free Church neighbours. But this was not that far outside dissenting Presbyterianism; his critical engagements were within Presbyterian theological controversies.

By the 1870s, however, that had changed dramatically. Where in 1857, for example, he celebrated and strictly observed Sunday as “the Lord’s Day, [as] a day of rest for man and beast”, by August 1879 he maintained that “Sunday is only a manmade day … All religion is of man’s manufacture”. Even his early focus on the universality of the Atonement – a significant feature of Morisonian theology – came under critique: “I am reading works on the Atonement”, he recorded in December 1853, citing particular biblical passages as textual proof of his position:

“I am firmly of the opinion Christ died and thereby made Atonement for every man – every human being. For the sin of Old Adam sunk the human race and the apostle says “that where sin abounds grace did much more abound’ [Romans 5, 20] and ‘that Christ tasted death for every man’ [Hebrews 2, 9] and ‘he is the propitiation for the sins of the whole world’ [John 2, 2]”

By the 1870s his reading patterns were quite different. And by 1883, after six or seven years of reading Charles Watts, Robert Ingersoll, and other free thinkers, Barry’s thinking had shifted ground significantly:

“I was in my Shop all day setting type for an article by Charles Watts entitled ’The Fall and Redemption’ and an able handling he gave it. In fact he knocked the fall and redemption into nonsense, which every sensible man and woman can easily see …. ‘Fall’, ‘Redemption’, ‘Inspiration’, ‘Atonement’, in fact the whole jumble of incoherent nonsense in ‘Theology’ is absurd … and ordinary people are coming fast to see it, and reject it in toto.”

If not explaining to us in any detail how Watts “knocked” these ideas “into nonsense”, Barry was absolutely clear in highlighting his own shifting worldview. Equally clear is his textual evidence, citing first the bible then later Watts. Indeed, text also enabled what might normally be experiential evidence. The “ordinary people … coming fast to see it”, upon whom Barry rested his belief in progress, were ordinary people in New York and Chicago, not Six Mile Brook – the people of his textual world.

So, we can see that Barry had undergone a radical change in his thinking on theology, and that that came about through his engagement with new ideas in the books he was reading. It also coincides with a shift in local booksellers moving their primary suppliers from Edinburgh and London to Philadelphia and New York, a shift that no doubt was related to the dramatic rise of coal trade shipping to the eastern seaboard. Can we see that trans-Atlantic shift in Six Mile Brook? Can we see him transmitting those old and new ideas into Six Mile Brook, the West River, and beyond? The typically asocial Barry was not a prime candidate for promoter of the unfaith, or much of anything really. He had some regular reading friends, notably Dr Murdoch Munro, with whom he had a generally amiable friendship clearly centred on books and discussion. He admired educated men, and judged them accordingly. When his neighbour William Sutherland died in the summer of 1857, Barry commended his faith, but not his education. “I think he was a true Christian, although not a very learned one”. Barry’s Christianity was profoundly textual and like most evangelicals he explored this faith through “the Word” of the bible; unlike most evangelicals, however, that deep, critical immersion in text and reading eventually pushed him to free thought. For Barry, learned status competed with faith as a marker of worth, but with his faith rooted in textual criticism the door to abandoning faith was wide open.

The diary gives us a very clear picture of the mill as a community hub. Barry certainly could be less than charming but most everyone in the community went there either to grind their grain, saw their wood, or purchase shingles, staves, or fenceposts. These conversations are almost completely inaccessible to us, but we get glimmers in the diary. “Kenneth Irvine was here at the mill and we had a long chat about the Bible and some other things”, reads a fairly typical entry from November 1877. Religion, and increasingly over the years, anti-religion, was the most common topic. “Many about the mill today”, he reported, in July 1883, “talking about the Bible, they are superstitious”. Politics too was common, notably in the period between the Quebec Conference in 1864 and the death of Nova Scotia’s anti-Confederation movement around 1870. Here, some of the talk was based on local public meetings, but the vast majority stemmed from their readings of the newspapers. The bases for his long discussion with his employee, Sandy Sutherland, in May of 1854 about “Nova Scotia railways and the war in Russia” [the Crimean War] no doubt also came from newspapers.

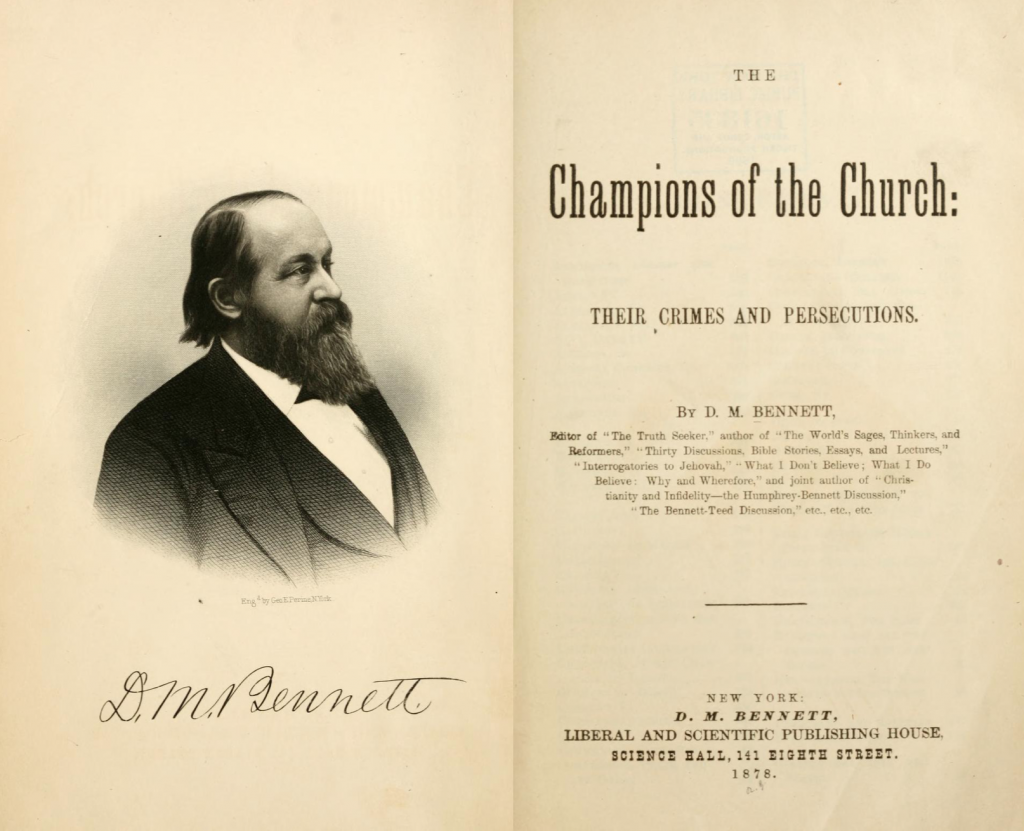

The focus of discussions, like the focus of his reading, was shifting. By the late 1870s, free thought and a fundamental critique of Christian theology also seem to have become common conversations around the mill. One evening his friend Munro came by and they discussed D. M. Bennett’s recent book: “Dr Munro was here this evening”, he noted in August 1877. “‘Champions of the Church’ was the book that occupied my attention most. It gives fearful accounts of Cruelty practised by one Christian on another. They are all tarred with the same stick it seems”. It’s hard to say how influential Barry was here – in other entries, Munro seems more intrigued than invested – but the miller was certainly bringing new ideas to everyday conversation in Six Mile Brook.

In all these discussions, Barry was always right. In town buying supplies in 1883, he “had some talk about Bible stories to various persons but [I] always came of conquerer [sic] by a long chalk. Most don’t know much, they are stupid and ignorant”. He wasn’t much of a proselyte, typically dismissing the ignorant and praising only those with whom he agreed. But he tried. “McDonald the miller came by this morning. I presented him with a Book of Tracts on free-thought. He is no bigot not a pious fool. He will learn”. There were numerous such discussions and it’s still clear that most involved an exchange of ideas and Barry loaning, selling, and sometimes even giving a suitable book. If he suffered no fools, and thus often spoke only to those already onside, Barry was nonetheless an active agent of intellectual exchange. In the market for ideas, he had a product and some willing customers.

We have a less clear sense of how many then purchased those ideas. The diaries and an account book give us only fragmentary clues on Barry’s reach, but if we take into consideration his place at the centre of the community (that is, as a miller, not as a social person!), his frequent trips to town where he almost always reported engaging with someone, and combine that with the fact that he was printing and binding dozens of the free-thought works (among much more), then he certainly had the potential to reach a lot of people.

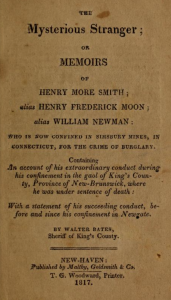

Precise numbers are scarce. But a single entry in the diary from April of 1884 offers a hint. “I sold [Johnny McLeod] a whole Back-load of Books – Henry More Smith and the family doctor, 3 doz of the former and 4 doz of the latter”. We don’t know that he printed these, but he was printing books and here at least he’s selling dozens of copies. He printed a wide range of materials and neither of the titles noted here were free-thought works. But he was tight with his money and however much he loved printing (a point he made several times) he wouldn’t cast type, print and bind works purely for the pleasure. It suggests that the miller on Six Mile Brook, who spent much of his time in his “little shop”, as he termed it, was not only a miller but also a printer, a bookseller, and very much a critical node in this tiny corner of the transatlantic world of books and idea. A decidedly uncharismatic proselyte, he was nonetheless an able aggregator and disseminator of everything from domestic self-help guides to radical free-thought works. James Barry brought distinctly modern ideas and debates into the back-country world of the West River. Six Mile Brook was a tiny place far from the colonial metropolis, but it was it was very much a centre of the modern world.