I always tell students that as historians we very often study ourselves – that is, that we pursue topics not just that interest us, but that speak to us about who we are, how we view the world and sometimes even where we came from. My earlier work on rural Nova Scotia was very much driven by my own family background. None of it was genealogical in any way – despite spending a fair amount of time in several large 19th-century Inverness County archival collections I don’t think I even stumbled upon any relations – but I always somehow knew I was studying “my people”.

Much of that conception revolved around three things: that my family were Acadians and Highland Scots, that they were poor, and that they were Catholic. These don’t provide me any essential features of identity – I grew up a middle-class suburban boomer and nominal Catholic – but it offers a framework for situating myself in the past. That my ancestors suffered at the hands of the British – Jacobites driven out of Scotland, Acadians driven out of Acadie/Nova Scotia – offered me a sense of my family’s place in the broader history of the Atlantic world.

Of course I didn’t know any of this growing up, and only put it together piecemeal as I both dabbled in some genealogy and taught the Atlantic world with a centre on Acadie. And over the past ten years I’ve dabbled more in the genealogy. I’ve found the first settler Samsons on the Lauzon seigneury across from Quebec, and one sons’s movement to Port Royal; I traced the MacInnis family from the Jacobite stronghold of Glenfinnan through the British army’s preemptive strikes against Jacobite villages during the Napoleonic wars to the backland farms behind Port Hood.

But I’d never found the time to explore my paternal grandmother’s side. That’s perhaps not surprising as I barely knew her. She died when I was 6, and my grandfather when I was 10. So all I knew of Katie George was what I was told: she was Irish and from Halfway Cove, Guysborough County. And that made sense. There are lots of Irish settlers in that are. And as a story – Irish girl meets Acadian boy, perhaps at a shared Catholic church in Halifax where they had both moved in the 1920s – fit a common pattern of the era.

Last fall, while in PEI waiting for a plumber, I saw tweets by Stephen Archibald about a weekend tour of the eastern shore of Nova Scotia and that prodded me to begin a quick look at my own eastern shore background. I had my grandparent’s wedding certificate and so I had the names of her parents: Thomas George and Mary Boudreau. (Oh look, I thought, her parents were another Irish-Acadian match. How very poor-Catholic-fisherfolk of them!) Both 29, Katie and Joseph married at St Mary’s Basilica in Halifax in 1925. Fancier digs than they knew growing up the children of fishers from L’Ardoise and Halfway Cove.

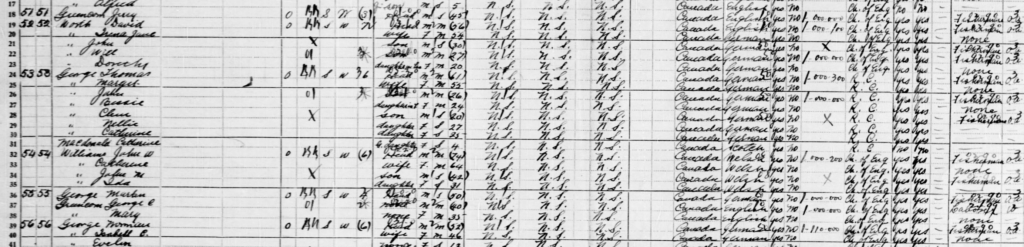

I began in the 1901 census. I found only one good match, a Thomas and Maggie George, with a daughter Katherine, 7 (about the right age) in Crow Harbour. Crow Harbour is no longer a registered place in Nova Scotia, but in the 1901 census it included a section of shore that included Halfway Cove. Close, I thought, but they were listed as German Anglicans, and with no other good matches I moved on to 1911, when Katie would have been around 15.

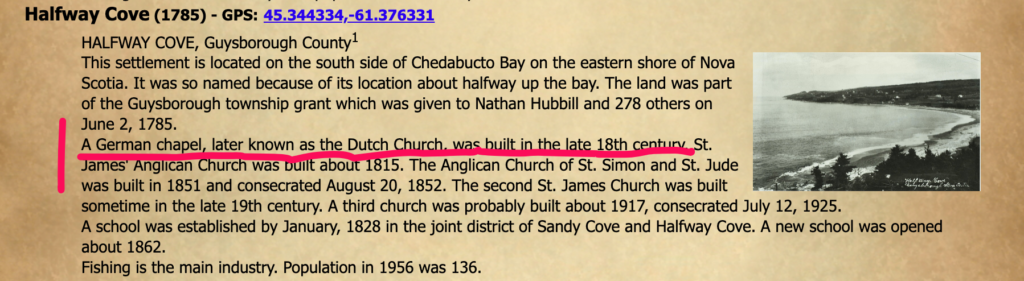

Same thing: really only one good match, and it was clearly the same family. The entry, however, was slightly different; they were “Dutch” – no doubt Deutsch, but still wrong, right? And, for that matter, I’d never heard of German settlements at this end of the province. Google, however, found an online Guysborough County gazetteer. And lo’ and behold, Germans in Halfway Cove:

Germans in Halfway Cove! Who knew? Well, obviously some people did, but I didn’t. And so I tried one more census, 1921, and it’s the same thing – the same family, though they’re finally “German” [including formerly French Maggie] – and now all Catholic – did the “Dutch” chapel close, and so they shifted to the the wife’s Catholic tradition? Or just errors?

But, as I’m bumbling about here, I’m also beginning to think, ok, so there’s less than 200 people in Halfway Cove, and that location is one of the few things I know for sure about her, and I keep finding this same near matching family and … and … my goodness yes, she was German! Or least her male lineage was German. And of course that means I’m part German (and not even part Irish! – well, actually a tiny bit – as I discovered later, Katie’s grandfather, Valentine, married an Irish woman, so I’m still one sixteenth Irish!). I continued on. I pursued Valentine, and discovered another Thomas and a Ludwig, and other new non-French, non-Scots names; I discovered a new dimension of me!

I take great delight in this, particularly as my partner Ingrid’s first-language is German, and I can now toss this around in conversation with her Germanophilic mother, Lilli. And I love, as a historian, being linked into another set of stories, ones that I’d not imagined to be part of my past. And I love that my past has this messier dimension. “My people” is seldom what we imagine.

But of course I also wondered, why did people describe Katie as Irish? Did she describe herself as Irish? Her mother was a Boudreau, so she was at least partly Acadian, and one grandmother was Irish, but that’s a slim claim. Maybe confused family lore (she died a long time ago [1967] and I have few known relations on that side of my family) – or perhaps it was a way to make her Catholic for a Catholic wedding?

Or maybe it was about World War 1? Maybe this young woman with a German name (if a German-Acadian family) felt she needed to hide that. It’s the angle that makes the most sense, and it’s the angle that most makes me wish I could ask her questions. Did she experience hostility in Halifax during the war? I know my military-aged Acadian grandfather did. Was this an extension of the same idea that prompted Berlin, Ontario to change its name to Kitchener, that prompted a wave of anti-German sentiment across the country? Lunenburg was not immune to this pressure (see Gerry Hallowell’s book “As British as the King”). We know many German-Canadians altered their names/associations, though “George” is not obviously German – and she’d have been fourth of fifth generation in British Canada. Of course, in Halfway Cove, that identity was well known, and maybe she carried that taint with her to Halifax. Maybe she carried it with her for the rest of her life.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day