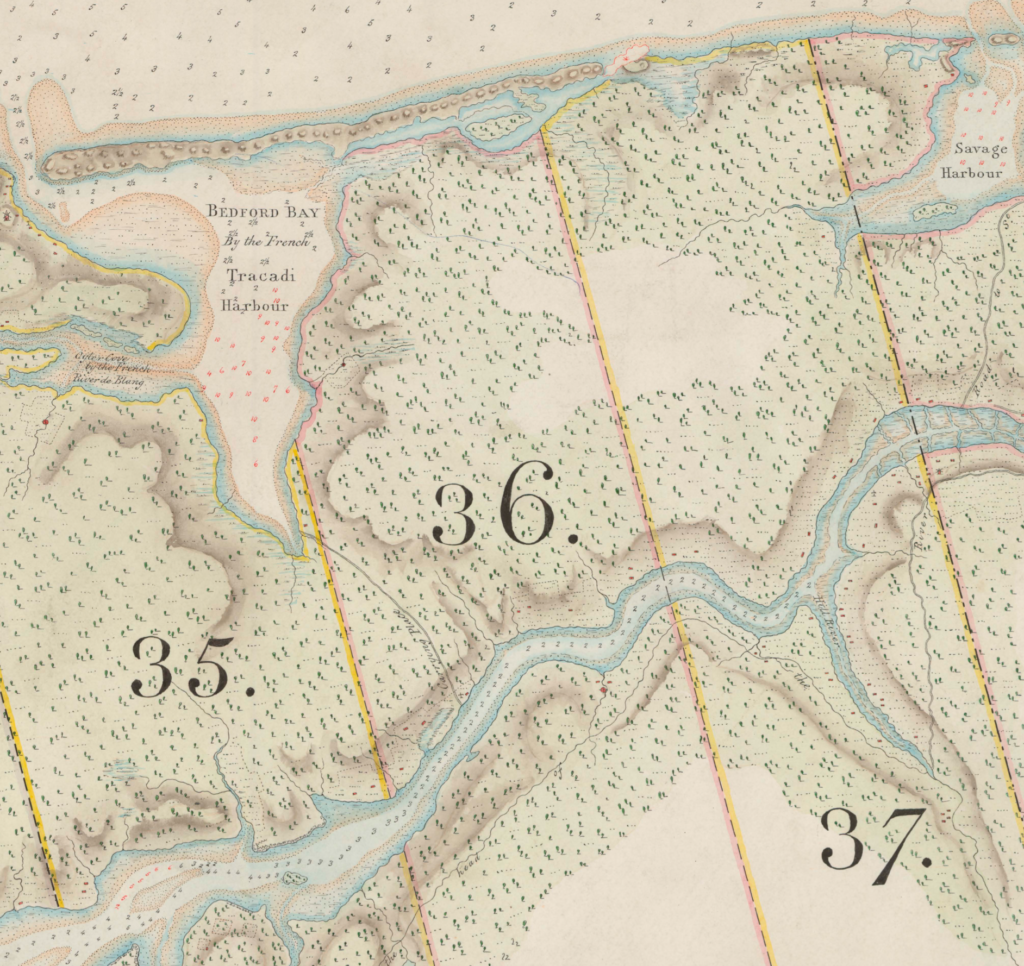

This term my fourth-year students will be building a website examining 300 years of land use in what is today east-central Prince Edward Island. We’re focussing mostly on lands that in the 1780s become the estate of Captain John MacDonald on lots 36 and 37 near the head of what is today called the Hillsborough River. The project aims to get at land-use by the three cultures we know utilised the land in that era – Mi’kmaw, Acadian, and British – as a way of assessing the productivity and sustainability of the area for human use. We will be assisted in this by Josh MacFadyen, the Canada Research Chair in Geospatial Humanities at the University of Prince Edward Island, who will join us for a class next week. Josh is conducting a series of energy profiles of 19th-century farms. Our task in this blog will be to identify and map some 18th-century Acadian farms that after their expulsion became some of those 19th-century British-era farms.

Before the expulsion of the Acadian population in 1758 during the Seven Years War, Prince Edward Island was Ile Saint-Jean, part of the remnants of Acadie after the British conquest of the peninsula. The island was also called Epekwitk, the land lying in the water, the largest of the islands of Mi’kmaw territory. Epekwitk’s history spanned millennia. Ile Saint-Jean’s settler history is short, really only less than forty years between 1720 and 1758. And even for much of that period, there was little settlement. Until 1748, and the peace following King George’s War and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle, the French population consisted of only about 800 people. The peace treaty, however, did not bring stability and British pressure on peninsular Acadians and Mi’kmaq, compelled many settlers to flee across what is today the Northumberland Strait to the relative security of French-controlled areas on Ile-Saint-Jean. By 1752, when Sieur La Roque, a French military official from Louisbourg, took a full census, the population had climbed to over 2600. The flood of refugees intensified and while we have no exact numbers the population may have been over 5000 by the time the British began expelling the entire population in 1758. This potted history goes a long way to explaining why so many of the settlers we’re about to examine had only been in the colony for two or three years, where some others had been there for decades.

La Roque’s census is an exceptionally rich document of life on Ile-Saint-Jean just a few years before the expulsion. It’s a narrative census, not tabular, and the officer from Louisbourg appears to have been both very careful in counting livestock and crops and yet also happy to wander from his narrow mission to occasionally extemporise on other issues: problems related to defenses, economic/trade policies that he noted hurt the settlers, and the suitability of lands for additional agricultural settlement. We’ll work from the transcribed and translated version published by the Public Archives of Canada in 1905 (volume 2).

Though not tabular, La Roque’s data is consistent, noting the [usually] male heads of household, their age, place of birth and how long they had been “in the country”. This was followed by the same information for the wife, and then the names and ages of the children, and servants if there were any. He then described the land, their livestock and what (and to some extent how much) they were planting. The following is typical entry:

Pierre Boudrot, ploughman [habitant laboureur], native of l’Acadie, aged 40 years, he has been two years in the country. Married to Marie Duaron, native of l’Acadie, aged 36 years.

They have two sons and seven daughters :

Firmain Boudrot, aged 7 years;

Jacques, aged 4 years;

Marie Blanche, aged 18 years;

Anne, aged 1 6 years;

Marie, aged 14 years;

Magdeleine, aged 12 years;

Marie, aged 10 years;

Nastazie, aged 8 years;

Ufrozinne, aged 6 years;

Judict, aged 12 days.

In live stock they have four oxen, three cows, three heifers, five ewes, two calves, one sow, six pigs, and ten fowls.

The land on which they are settled is situated on the Riviere des Blancs, it was given to them verbally by Monsieur de Bonnaventure. On it they have made a clearing of eight arpents in extent and have sown five bushels of wheat, eight bushels of oats and one bushel of peas.

So, that’s very good data: location (riviere de Blancs – today’s Johnston’s River), names, ages, how long settled (not long!), where born (“L’Acadie”, thus their brief tenure is likely because they’d fled peninsular Acadie/Nova Scotia), some sense of their legal standing (land was “given to them verbally”), the extent of their land and improvements (arpents), and numbers on their crops and livestock.

Mapping that specific site, however, is tricky. We can offer a pretty good guess – the river is only a few km long and there were only about ten households on it – but it would be quite general. Moreover, we’re much less sure of their suitability for comparison as the family were only on the land for a few years. As we can see from this Google satellite image, the land is heavily farmed today, and no doubt was in 1861 too, but we don’t have a good sense of this as a functioning farm in 1752.

But we can find some families that had been on the island much longer and there we can get a much better sense of a functioning farm. And, we even have a fabulous map that indicates the locations of farm families on the la rivière du Nord Est. Though not from 1752 (it’s from 1730), judging by ages and times they were in the colony it seems at least some of the families from 1752 can be located on the 1730 map. Thus we have a very good sense that these families probably had farmed those sites for over 20 years – a much better sense of such farms existing as a kind of agro-system that we might compare to a later, also longer-standing farm.

Even in this low-res version, you can see several clusters of settlers: one at Port La Joye (across from present-day Charlottetown, on the left of this west-oriented map), and two further up the river (near what is today Mount Stewart). We can match several of those names with entries on the 1752 census. Here I’ll simply note two from the northeastern clusters. I could trace only one name from the Port la Joye cluster, Joseph Pretieux and his family, and they appear to have relocated to riviere du Ouest. Speaking of that point of land, Louis de Franquet, a French engineer reporting on Ile Saint-Jean in 1751, noted “avant la dernière guerre toute la partie défrichée était en culture” , but now “ils soient dans l’appréhension qu’à la moindre rupture avec les Anglais, leurs travaux ne deviennent infructueux”. Pretieux and his family found a better location.

Up the river, we find other possibilties, such as Bathelemy Martin:

Barthelemy Martin, ploughman, native of l’Acadie, aged 42 years; has been in the country 30 years. Married to Magdeleine Garret, native of l’Acadie, aged 38 years.

They have six sons and four daughters : —

Pierre Paul Martin, aged 20 years.

Charles Michel, aged 18 years.

Francois, aged 16 years.

Jacques Christophe, aged 14 years.

Joseph, aged 12 years.

Jean Felix, aged one year.

Marie Joseph Martin, aged 13 years.

Euphrosinne, aged 9 years.

Marie Joseph, aged 7 years.

Jeanne, aged 3 years.

They have the following live stock : four oxen, four cows, four heifers, nine wethers, eleven ewes, five pigs, nine fowls.

The land on which they are settled is situated as in the preceding cases and was given to them by grant from Messieurs Duvivier and Degoutin. They have made a clearing on it where they have sown forty bushels of wheat, fifteen bushels of oats, and half a bushel of peas, and made fallow land for the sowing of twenty bushels more.

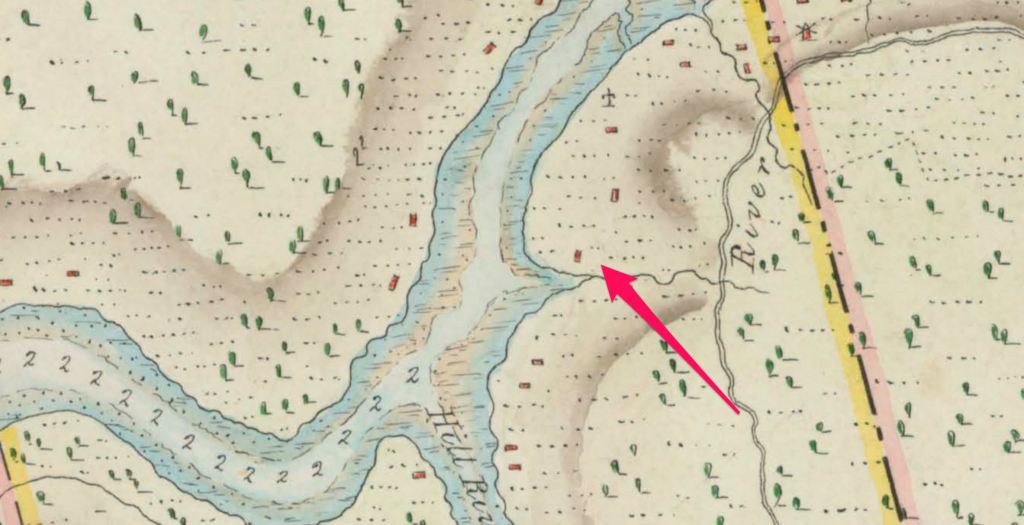

And on the 1730 map we find a Barthelemy Martin, just past the fork of the riviere Pegiguit [today’s Pisquid River]. Barthelemy and his wife Magdeleine were 20 and 16 when the map was made and two years after would have a son, Pierre Paul, 20 in the 1752 census. They seem a good match, and their land is easily located just north of the fork in the river.

This bend looks consistent with a Google map of today:

Zooming in closer, the little stream indicated just below Barthelemy’s name maybe this small inlet (a). In which case his land would be approximately the block at (b).

Evidently the marshland so sought after by the Acadian families is much less prized now as none of it is farmed.

And, if we’re right in all this, we can then go to Samuel Holland’s 1765 map, the first British map of the island. Exceptionally well-crafted and made just seven years after the French population was removed, we can point to this red square as likely representing the remains of Martin’s farm house on what was now designated Lot 37. We don’t know for certain that Holland mapped houses/remains so closely – or as precisely as we’re assuming – but we know that in general he was careful and commented on remaining buildings.

LaRoque’s account suggests Barthelemy and Madeleine had one of the more productive farms on the river. They held four oxen, four cows, four heifers, nine wethers, eleven ewes, five pigs, and nine fowls. They were settled on the south side of the river with a grant from Messieurs Duvivier and Degoutin. They had made a clearing on it where they had sown forty bushels of wheat, fifteen bushels of oats, and half a bushel of peas, and made fallow land for the sowing of twenty bushels more. After more than twenty years on that land they had a substantial farm. Walking the fields on that section of the river one year earlier, Louis de Franquet was certainly impressed: “que tous les terrains que nous avons été à portée de voir et de parcourir promettaient une récolte en froment, avoine, pois et autres denrées, aussi abondante et de la même beauté et qualité qu’en France”.

The windmill Holland depicts just up the river from Martin may be Jacques LeBlanc, 57, native of l’Acadie, and his wife Cecil le Dupuis, native of l’Acadie, aged 55 years:

Their live stock consists of eight oxen, six cows, one heifer, three calves, two bulls, two horses, five ewes, three sows, three pigs and twenty-five fowls.

The land on which they are settled is situated on the south side of the River du Nord-Est of Port La Joye. They have sown on it ten bushels of wheat, one bushel of oats and seven bushels of peas, and they have fallow land sufficient to sow twelve bushels of seed; they also have a saw mill.

LeBlanc was noted at Riviere du Moulin-a-scie [Sawmill River], situated on the south side of the Riviere du Nord-Est. Presumably the windmill icon is a standard “mill” symbol, not specifically representing a windmill.

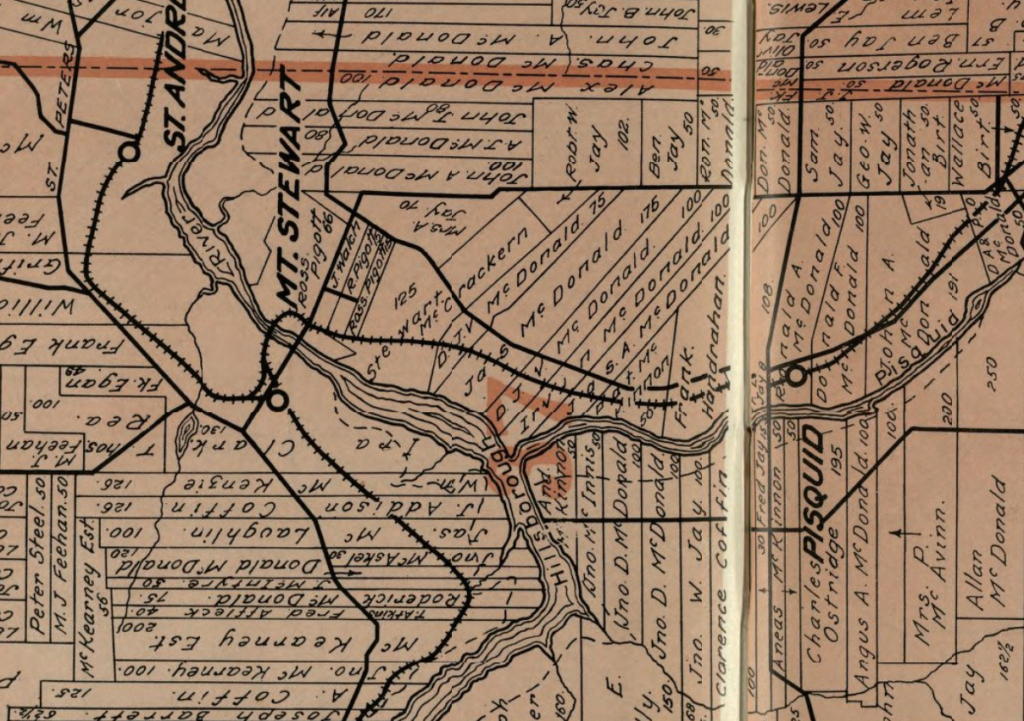

The hope here is to carry this work forward into the British era. That bend on the river corresponds to what will become lots 36 and 37. They came to be owned by Captain John MacDonald of Glenaladale (and managed by his sister Helen). They settled Highland Catholics (the irony of the displaced Scottish Catholics replacing not Mi’kmaw people but displaced Acadian Catholics!) in the 1770s and Loyalists in the 1780s and 90s. The intensification of land-use beginning at this point is tremendous. The marshlands that attracted the Acadians to that area was also valuable to the British-era settlers, and we can see commons-based approaches to its use well into the 19th century. At the same time, the demographic surge we see after 1770 points to much more extensive holdings where upland sites became predominant. Through historical maps and the census, we can trace those holdings and their shifting approaches to land-use.

We can see these locations quite clearly on Lake’s 1863 Topographical Map of Prince Edward Island .

We might possibly carry this into the 1920s with the 1921 census and Cumming Map Co, Atlas of Province of Prince Edward Island, Canada and the world Toronto (Toronto, Cumming, 1924).

Finally, there is a small Mi’kmaw reserve at Scotchfort, across the river and a few hundred metres southwest of the these farm lots. Such salt marshes were important resource centres for Mi’kmaw peoples across the region. The Scotchfort reserve, created in 1879, was described as being “near the usual Mi’kmaq place for fishing and shooting”, and thus seems to have been a traditional hunting location. There’s a very good chance that this exact site was once a marsh utilised by the Mi’kmaq and that the presence of those Acadian farms represents some accommodation they’d made on dividing access to the river’s resources. Franquet’s 1751 report tells us that such agreement existed west of this location on what is today the Wilmot River, near Bedeque. Though with slightly less precision, it seems clear we can still describe this bend on the river as almost certainly a long-term Mi’kmaw site. That’s at least three hundred years of continuous occupation and use, by different peoples. Exploring that comparative possibility looks entirely possible.

We’ll leave this later work to the students in Josh’s lab, but the possibility of identifying some individual farms whose production we can trace across 300 years is an exciting prospect. Adding to the statistical possibilities with some softer data – such as Franquet’s observation (in the very same section of the river) that “nous parcourûmes ces différents champs et, au vrai, jamais récolte dans les meilleurs cantons de la France ne promit davantage” – might allow us an assessment of an “agrosystem” that was efficient and sustainable. It was a very particular agrosystem, to be sure, but not one imagined merely from a utopian vision.